Imagine trying to save a forest without ever talking to the people who live around it. Or studying a river’s chemistry while ignoring the farmers upstream who depend on its water. That’s kind of what conservation science has been doing for decades—zooming in on the “hard” sciences like geology, hydrology, and ecology, while leaving human behavior, culture, and economics as a side note. But there’s a new shift happening in what’s called Critical Zone research (the study of Earth’s outer layer where rock, soil, water, air, and life interact). And here’s the kicker: weaving social science into it could completely change the way we protect ecosystems.

Table of Contents

What is the Critical Zone, Really?

Think of the Critical Zone as Earth’s life-support system. It stretches from the tree canopy down to the bedrock and covers all the spaces where soil forms, rivers flow, microbes thrive, and plants take root. It’s literally where life meets geology. Scientists have spent years digging, drilling, and monitoring this zone to understand how it works.

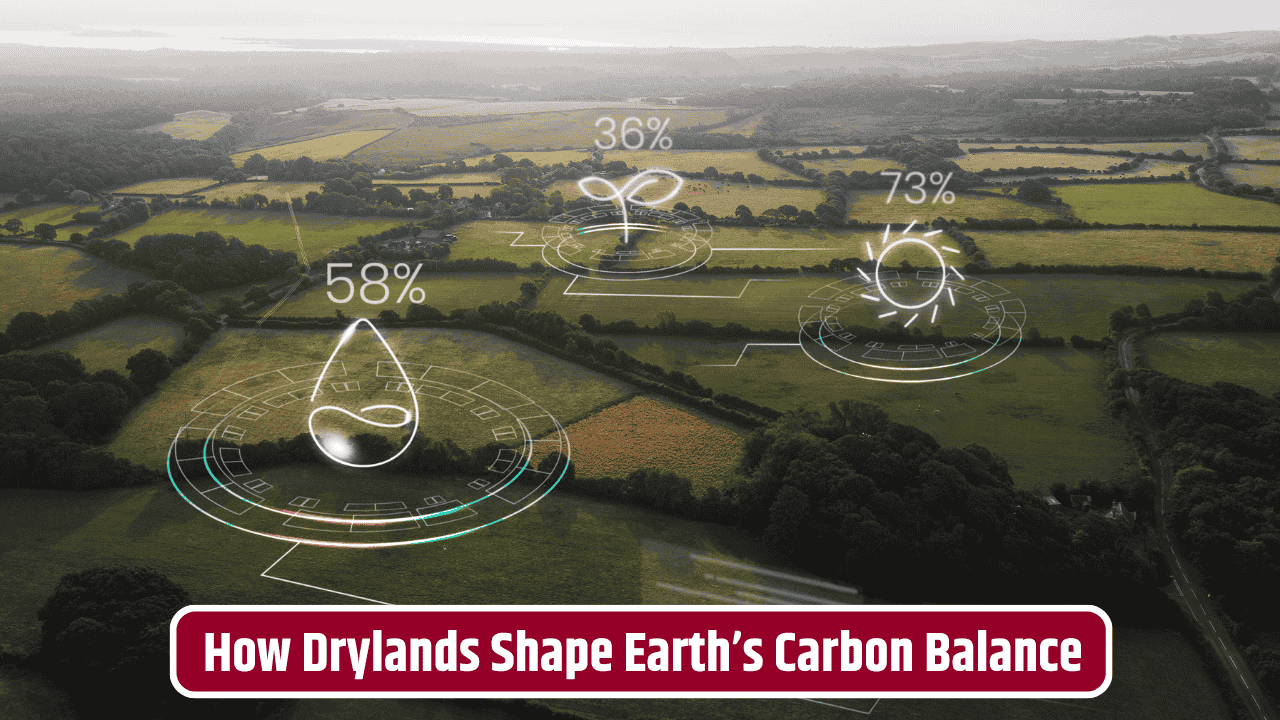

The U.S. National Science Foundation has been funding Critical Zone Observatories (CZOs) to track these interactions. Their work is eye-opening—showing how water cycles connect with soil health, how carbon moves through the system, and even how human activity leaves fingerprints on natural processes.

But here’s the catch: ecosystems don’t exist in a vacuum. People farm, build, burn, mine, and manage land in ways that affect every square inch of the Critical Zone. And that’s where social science walks in.

Why Social Science Belongs in Conservation

Social scientists ask questions that data sensors can’t. Why do farmers keep planting water-intensive crops in drought-prone areas? What cultural beliefs shape forest use in rural communities? How do economics and politics push people toward (or away from) sustainable choices?

Without these answers, conservation often falls flat. Policies get written, technologies get introduced, but if they don’t make sense to the people on the ground, nothing changes. For example, in India, community-led water conservation projects succeed not because of fancy tech, but because locals are involved in planning and decision-making. Similar lessons echo across Africa, South America, and even rural America where farmers respond better to peer-to-peer programs than to government pamphlets.

The Science–Society Bridge

The exciting part about integrating social science into Critical Zone research is that it builds a bridge. Imagine hydrologists, geologists, and sociologists working together, layering data on rainfall with surveys on how communities use water. Suddenly, conservation isn’t just about protecting land—it’s about designing solutions that stick.

Here’s a simple breakdown:

| Field | Contribution to Critical Zone Research |

|---|---|

| Geology | Maps bedrock, soil layers, and erosion patterns |

| Hydrology | Tracks water flow, storage, and contamination |

| Ecology | Studies biodiversity and ecosystem resilience |

| Economics | Examines resource use, incentives, and trade-offs |

| Sociology | Explores cultural practices, community behavior |

| Policy Studies | Analyzes governance, rights, and regulations |

See how that last column makes all the difference? It moves the research from “what is happening” to “what we can actually do about it.”

Real-World Impact: From Theory to Practice

If you’ve followed climate and conservation policy, you’ve probably noticed a growing emphasis on “nature-based solutions” and “community engagement.” This isn’t a buzzword trend—it’s recognition that without integrating social dynamics, conservation collapses.

Take watershed management in California: studies showed that involving local water boards and community groups in decision-making improved compliance and reduced conflicts. Or look at forest preservation in Nepal, where community forestry programs have been credited with restoring degraded landscapes while boosting livelihoods. These are living examples of science and society converging.

Challenges Along the Way

Of course, mixing social science with geology isn’t simple. Different disciplines speak different languages—literally and academically. A geochemist might measure nitrate levels, while a sociologist might interview families about fertilizer use. Getting these datasets to “talk” to each other takes effort, funding, and a shift in mindset.

And then there’s the policy side. Even with solid interdisciplinary research, political interests often hijack conservation priorities. Social science can illuminate these power dynamics, but it can’t erase them overnight.

Why This Could Change Conservation Forever

Here’s the bold claim: integrating social science into Critical Zone research could redefine conservation from the ground up. Instead of one-size-fits-all solutions, we’d get tailored strategies that actually respect local realities. Instead of short-term fixes, we’d see long-term resilience—because when communities are part of the process, they become stewards, not just beneficiaries.

It’s like moving from treating symptoms to addressing root causes. Conservation isn’t just about saving trees and soil—it’s about saving the relationship between people and the environment they depend on. And that relationship is complicated, messy, and deeply human.

Fact Check

Critical Zone research is a real and well-funded scientific initiative. The National Science Foundation (NSF) supports multiple Critical Zone Observatories across the U.S. (NSF overview). Studies on integrating social science into earth systems research have been published in credible journals like Nature Sustainability and Frontiers in Environmental Science. While the claim that this approach will “change conservation forever” is an opinionated framing, it’s based on emerging evidence showing better outcomes when social dynamics are considered in conservation planning.

FAQs

What exactly is Critical Zone research?

It’s the study of Earth’s surface layer where rock, soil, water, air, and life interact—essentially the zone that sustains ecosystems and people.

Why involve social science in environmental studies?

Because human decisions—driven by culture, economics, and politics—directly shape ecosystems. Ignoring that leads to ineffective conservation.

Are there examples where this integration worked?

Yes, from community forestry in Nepal to collaborative watershed management in California, social-science-informed approaches have shown success.

Is this approach recognized by governments?

Increasingly, yes. The NSF and European Union’s Horizon projects have both emphasized interdisciplinary research in environmental studies.

Does this mean traditional science is less important?

Not at all. Hard sciences remain essential for understanding natural processes. Social science adds the human dimension that makes solutions workable.